By 1525, Florence was sufficiently established as a glassmaking center that the importation of outside glass was forbidden. In 1567, Cosimo de' Medici (1519-1574), the greatest arts patron of his era, arranged, with the permission of the Venetian government, to establish a Venetian-style glasshouse in Florence.16 Luigi Bertoli, a maestro from Murano, was given a 14-year contract to produce cristallo17 in the Venetian style. To an unprecedented degree, the patronage of Medici (and succeeding members of his family) tied Venetian-style glassworking to both the fine arts (drawing and sculpting) and scientific research.

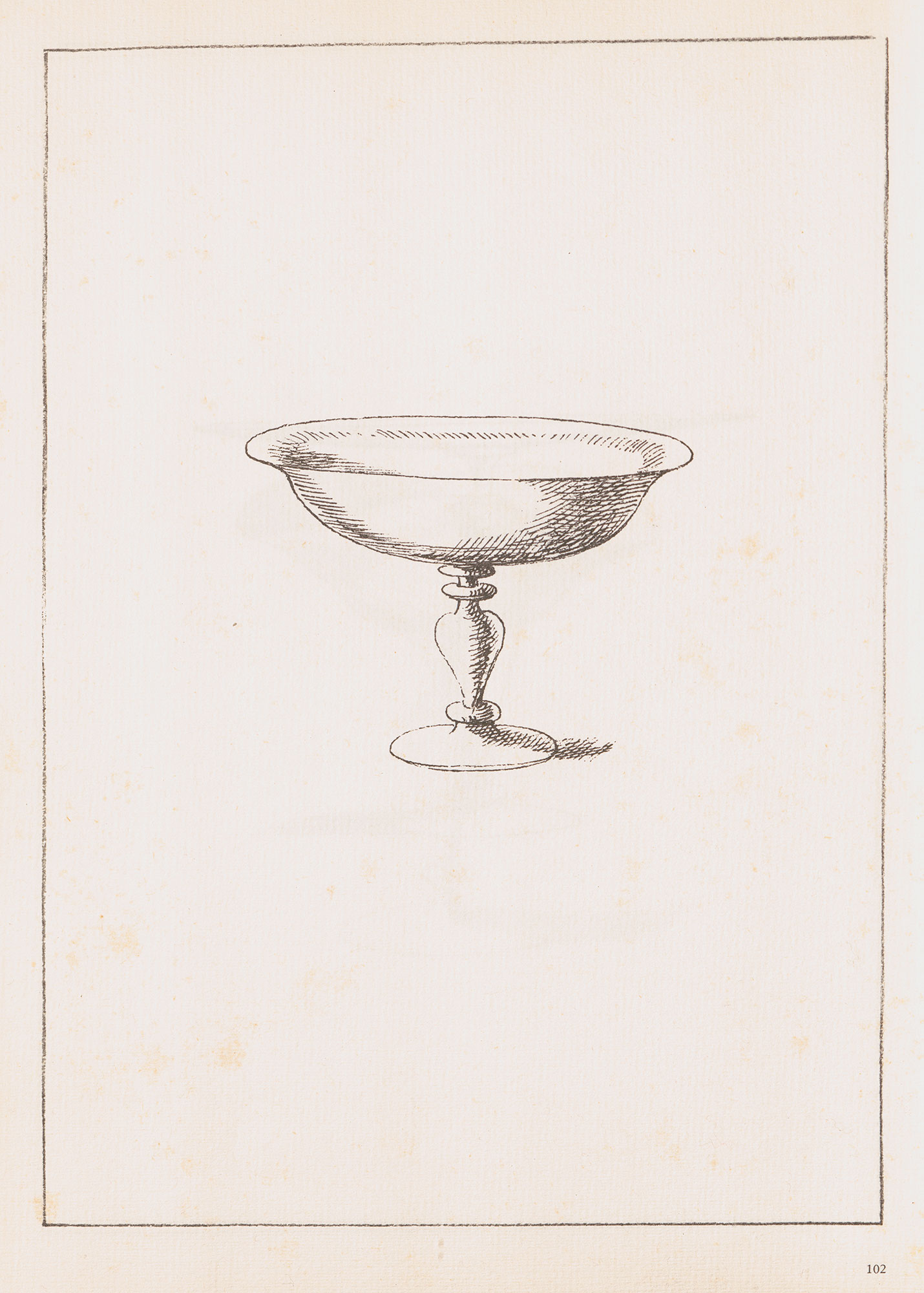

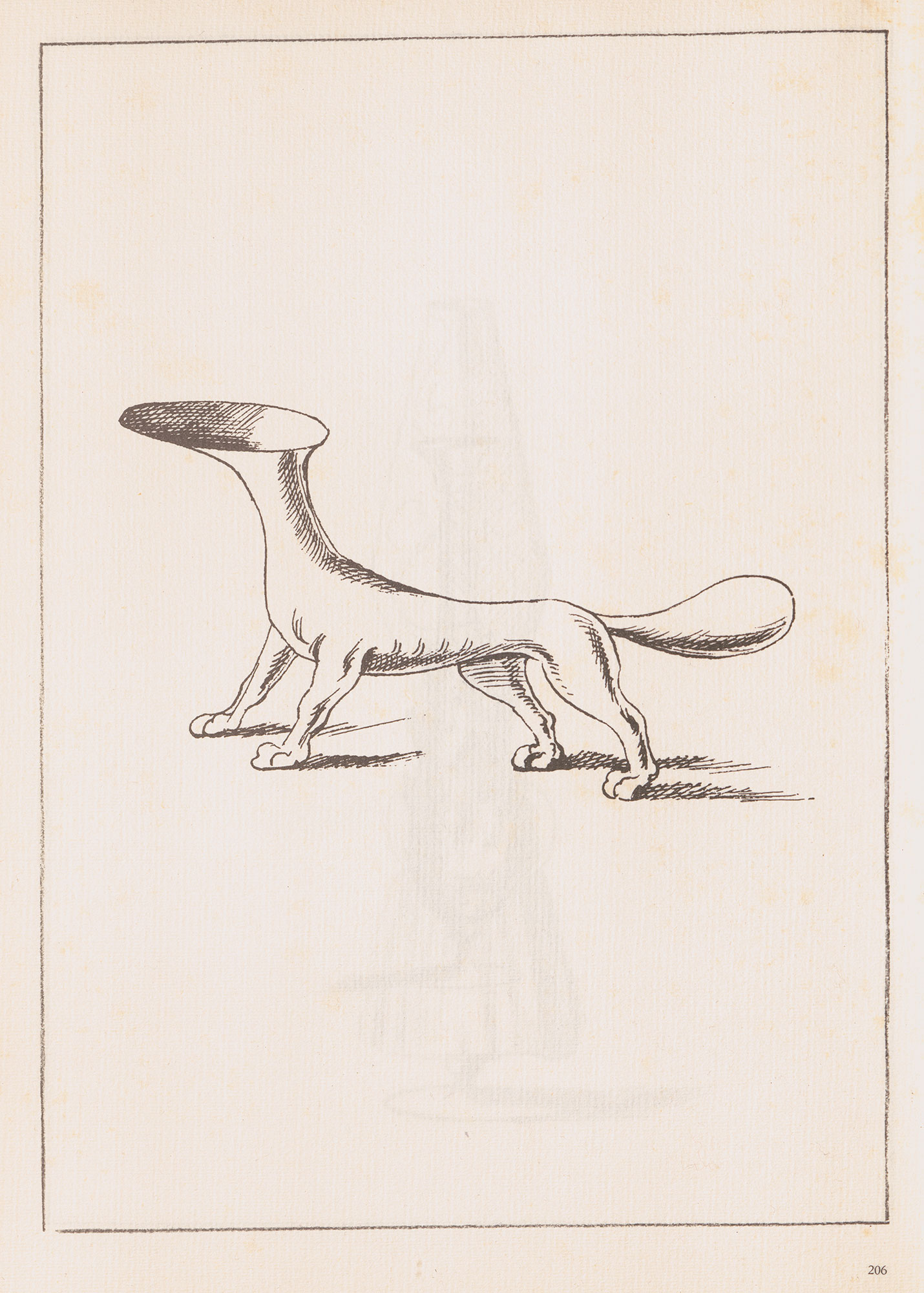

The connection with the fine arts was made by commissioning major court artists to create designs for the glassworkers to realize in cristallo. One of these artists, Giovanni Maggi (1566-1618), produced four volumes of drawings that range from conservative, traditional forms (Fig. 19) to perhaps the most fantastic shapes imaginable.18 Some of the latter are unlikely to have been made, however skilled the artisans (Fig. 20).

In regard to the scientific connection, also under Medici's patronage, the Santa Maria Novella Pharmacy (founded in 1221) was, no doubt, one of the glassblowers' customers, purchasing jars for storing chemicals and containers for medicines. Later, the Accademia del Cimento, established in 1657 by Galileo's students, commissioned glass scientific instruments, including thermometers, barometers, and hygrometers. The glassworkers used a combination of furnace glassblowing and flameworking (or lampworking) to fabricate extraordinarily elaborate structures (Fig. 21).19