Like the 2016 electronic resource The Techniques of Renaissance Venetian Glassworking, this e-book presents my thoughts about how a selection of historical glass objects may have been made some 300 to 500 years ago. In this second publication, I consider glass of a similar style and period that was made in a wide variety of European locations other than Venice (Fig. 1). The craftsmen may have been itinerant Venetians or perhaps local craftsmen who had been trained by skilled Venetians, or a combination of the two.

Preface

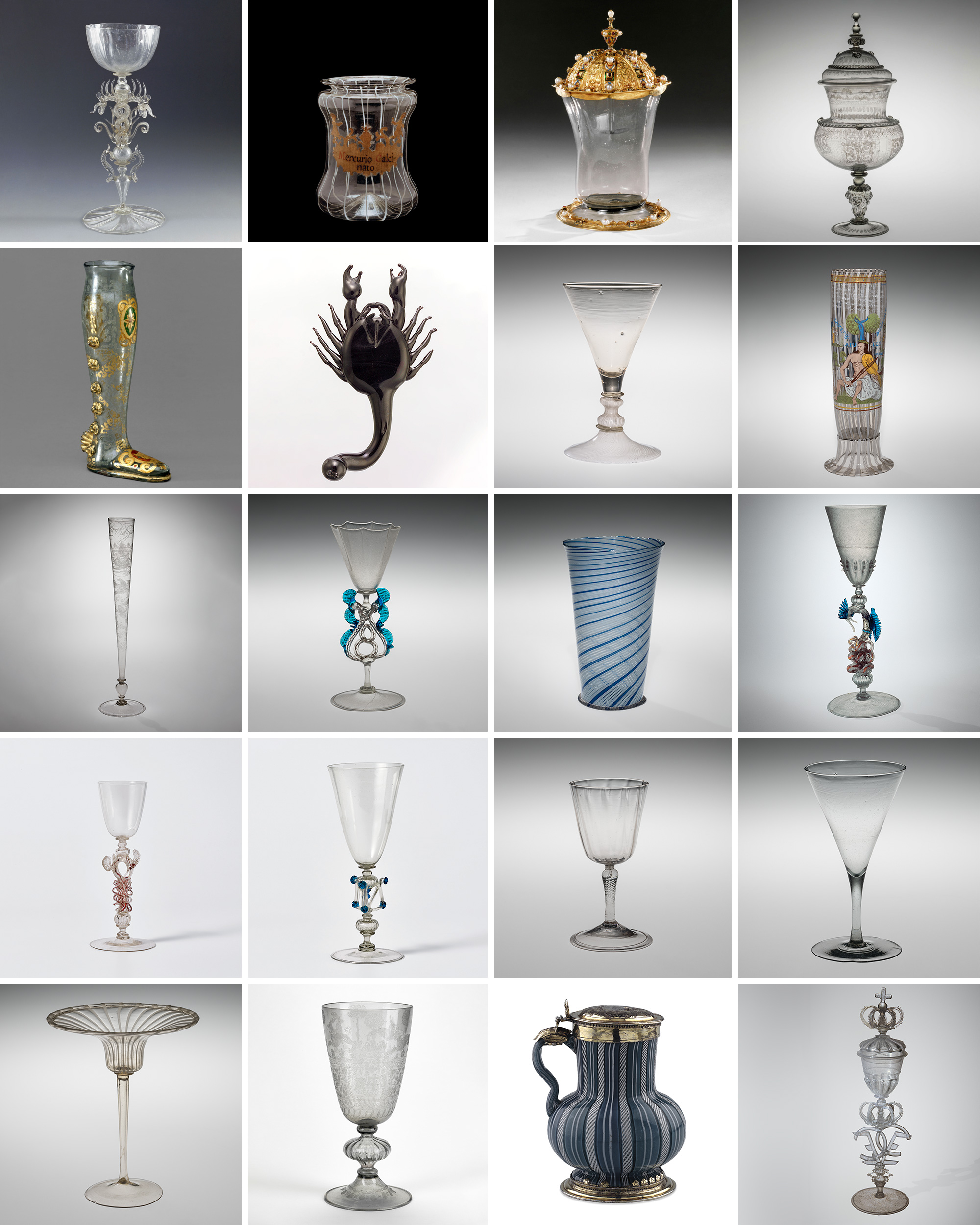

The 20 representative objects from nine glassworking centers around which this e-book is centered.

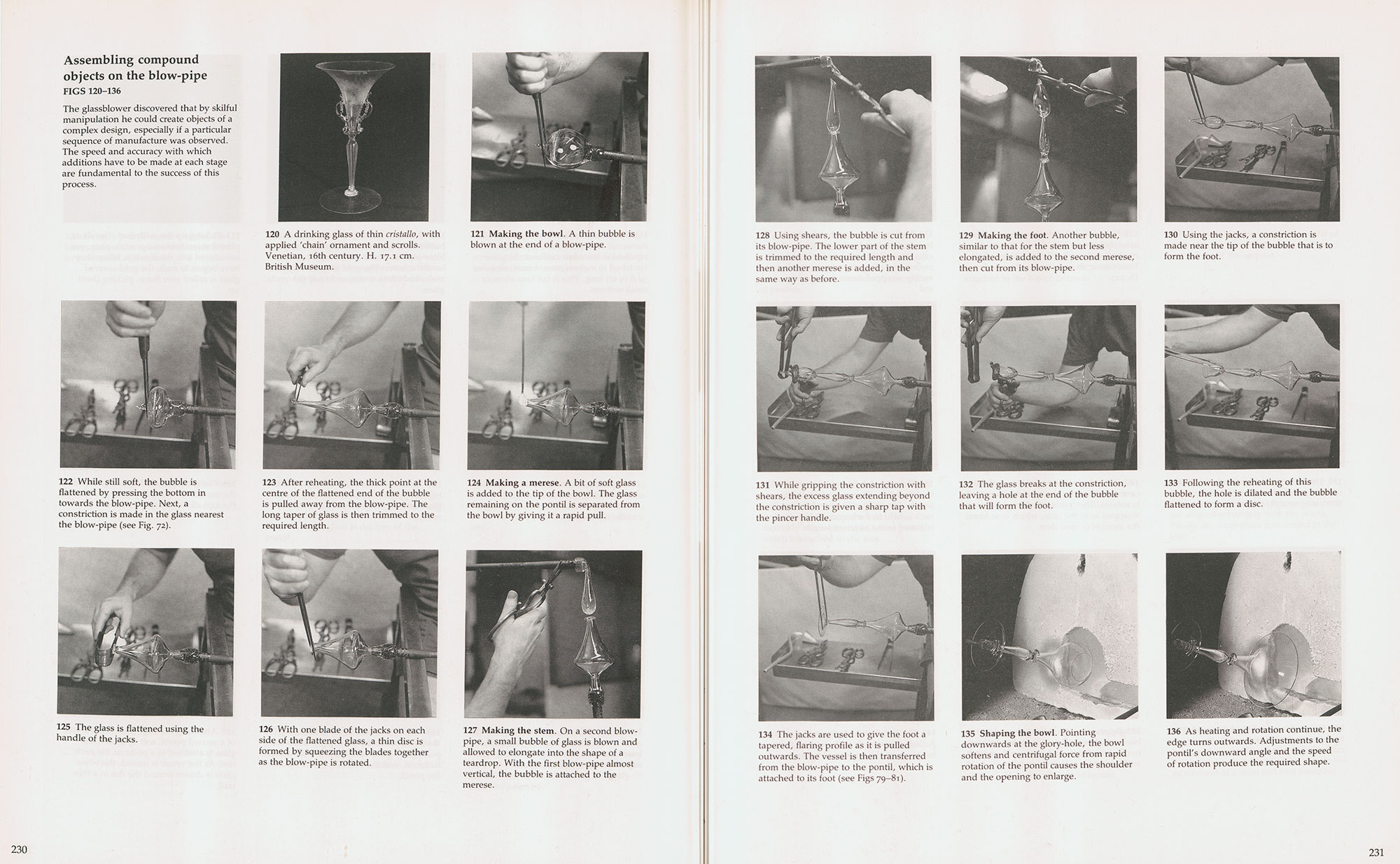

By far the most important content is to be found within the 20 new videos contained herein. Greatly superior to sequences of still photographs with captions that seek to depict swiftly moving processes (Fig. 2),1 videos capture an enormous amount of data while also conveying the inexorable forward movement within a very limited span of time that is a hallmark of virtuoso glassblowing. If one picture is worth a thousand words, one well-made video is worth a thousand pictures!

Pages 230 and 231 from William Gudenrath, “Techniques of Glassmaking and Decoration,” in Five Thousand Years of Glass, ed. Hugh Tait, London: British Museum Press, 1991. Photo: © The Trustees of the British Museum. Photo 121-136 taken by Steven Barall.

Happily, there are many recent publications that can be used to augment this study. Some of them are concerned with the archaeology and archaeometry (chemical analyses, etc.) of Venetian-style glass made between about 1500 and 1700. In reviewing the discussions of the 20 examples and their respective videos, the reader who wants more in-depth information will be directed to the most up-to-date works on each country’s Venetian-style luxury glass production.

For background information of a somewhat more general nature, the reader is unhesitatingly urged to acquire and become familiar with Beyond Venice: Glass in Venetian Style, 1500–1750, by Jutta-Annette Page, with contributions by five other scholars who are experts in various aspects of this field, published by The Corning Museum of Glass in 2004. It is the catalog that accompanied the Museum’s special exhibition of the same name in the same year (Figs. 3–6). It would be impossible to recommend a better companion text for this online resource. It and all of the other publications cited in this e-book are available on the website of the Museum’s Rakow Research Library.2

Entrance area of exhibition Beyond Venice: Glass in Venetian Style, 1500–1750 at The Corning Museum of Glass, May 20–October 17, 2004. Photo: The Corning Museum of Glass.

"Venice" area of Beyond Venice exhibition. Photo: The Corning Museum of Glass.

"Austria" area of Beyond Venice exhibition. Photo: The Corning Museum of Glass.

“Spain” area of Beyond Venice exhibition. Photo: The Corning Museum of Glass.

The videos that are the centerpiece of this publication represent one highly personalized way of re-creating the original blown glass objects—or, more correctly, re-creating the processes by which I think they were made. Here, as in all of my historical re-creative work, my intention is to focus on generating information rather than simply making objects.

My working methodology is straightforward.3 First, I closely examine the original piece in question. If possible, this is done with the object “in hand.” I seek parallel objects to look for common features and differences within the type or genre. Any specific evidence of the manufacturing process is noted. This would include such things as toolmarks, the distortion of bubbles trapped in the walls, and patterns of variation in the wall thickness of the glass. In short, I look for anything that can shed light on the order of operations and subtle manipulations that the glassblower employed hundreds of years ago.

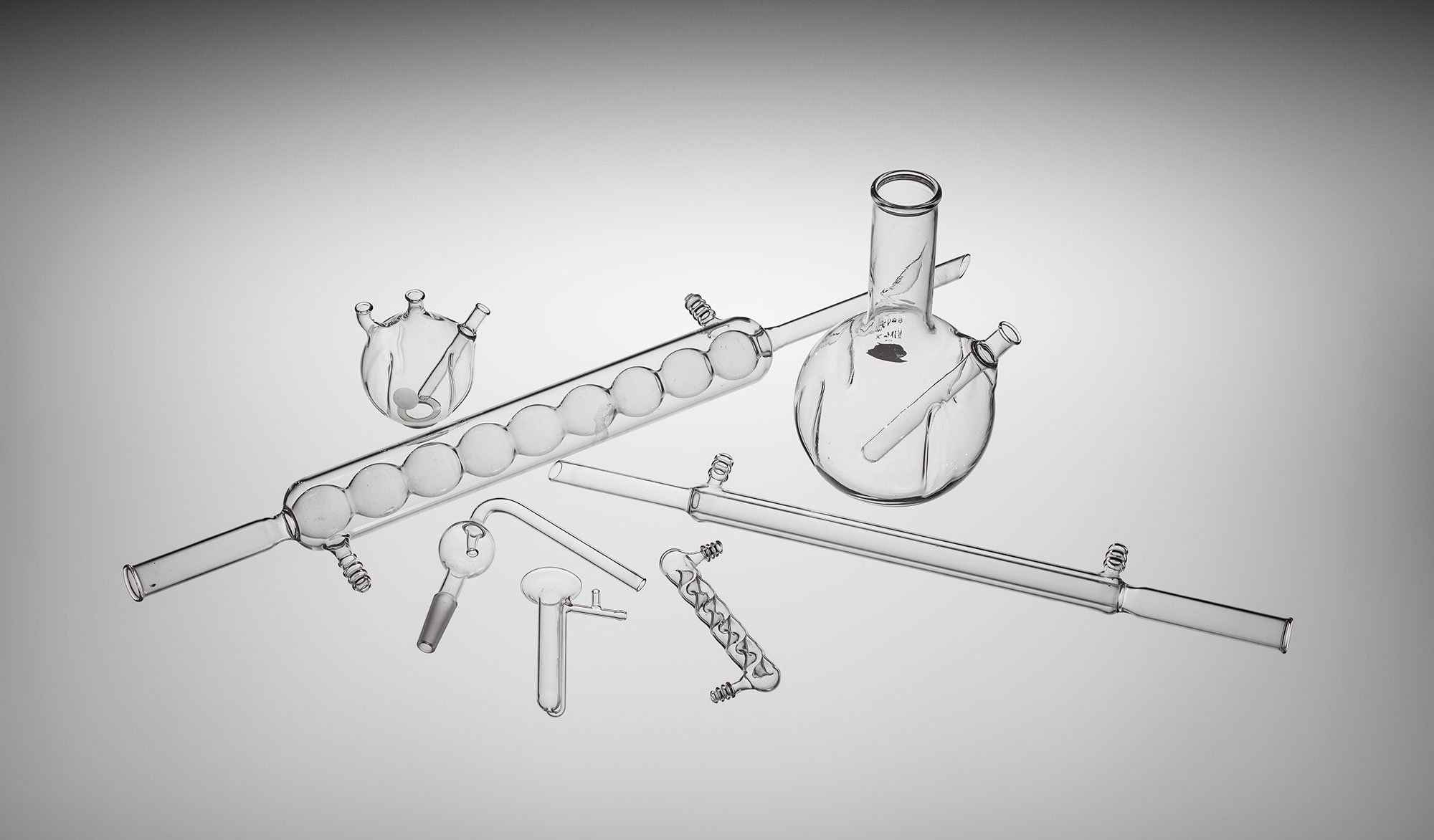

Next, I offer several hypotheses as to how the object could have been made. The many options are narrowed by my accumulated experience of working with molten glass and by my curiosity about historical glass for well over 50 years (Fig. 7). I try to consider any reasonable possibilities.

Selection of scientific glassware made by William Gudenrath, borosilicate glass, flameworked. U.S., Houston, Texas, 1963–1967. H. (smallest) 8.5 cm. Photo: The Corning Museum of Glass.

Finally, I conduct experiments at the glassworking furnace. There, I test the hypotheses and evaluate the results, looking for similarities and differences in the features thus created, in comparison with what is seen on the original object. This process, which is at times frustrating, can occupy days, weeks, or even months (when I am working intermittently on a problem). Eventually, a credible working method reveals itself, along with an object that shares many of the characteristic features of the artifact.

It is only at this point that I am ready to claim that this specific sequence of procedures is likely to reflect how the original piece may have been made. The importance of this statement, reflected in the phrase “may have been made,” cannot be overemphasized. Because there are no detailed period descriptions of glassblowing processes, my conclusions are admittedly nothing more (or less) than well-informed speculation. But however subjective this working method may be, I value its results much more than the untested, unsupported conjecture with which much historical glass literature abounds.

My striving for authenticity has limits. The positioning of the equipment and the fact that I work entirely alone (except when pulling multi-yard-long canes!) are my personal, idiosyncratic preferences and undoubtedly not true to original methods. The best illustration of 16th-century Venetian glassblowing, a painting by Giovanni Maria Butteri (Florentine, 1540–1606) in the Pitti Palace in Florence (Fig. 8), shows multiple craftsmen working without the relatively modern glassblowing bench that I use in my work. Instead, those workers sit or stand at the mouth (or working hole) of the furnace, apparently engaged in a coordinated endeavor. In lieu of a bench, the blowpipes and punties (or pontils) are rolled on a board attached to the top of the right thigh.

Giovanni Maria Butteri (Florentine, 1540–1606), The Medici Glass Workshop (detail). Palazzo Vecchio, Studiolo of Francesco I, 1570. Photo: Scala/Art Resource, NY.

By contrast, my equipment setup, together with my strictly adhered-to choreography (as can be seen in the videos), allows me to comfortably execute all of the required procedures entirely without assistance. While I make no claim that this approach is true to the period, I am confident that the action that takes place at the ends of the blowpipes and punties is very much like what took place in a Renaissance Venetian or Venetian-style glasshouse.

Similarly, the glass that I use is not formulated to closely replicate old Venetian glass, but it is nevertheless a long-working soda-lime glass that is probably not terribly different in temperature/viscosity characteristics from the glass that was employed by those earlier artisans.

The furnace seen in the videos (the original version of which I built with a colleague in 1981) is of the type known as a pot furnace, fired with forced air and natural gas (methane). During the manufacturing process, like the workers depicted in the Butteri painting, I reheat the object directly over a ceramic crucible filled with molten glass contained within the furnace. Thanks to its great thermal mass, this promotes a uniform source of radiant heat in addition to the voluminous hot gases that, swirling about, also heat the object by conduction—that is, by direct contact. In sharp contrast, a wood-fired furnace creates a much smaller volume of gaseous products of combustion: here, the gentler heat source necessitates reheating durations that are up to twice as long as those required for the same processes in a modern, gas-fired furnace (Figs. 9 and 10). Lastly, working directly over the glass facilitates the frequent gathering of additional glass for the many parts of complex objects, such as dragon-stem goblets: the molten glass is always just an arm’s reach away.

William Gudenrath working at wood-fired glassworking furnace in Velzeke, Belgium, September 2018. Photo: David Hill.

Detail of Figure 9. Photo: David Hill.

For better or worse, just as there can be no “definitive” way of, say, playing a Beethoven piano sonata, historical re-creative work of this nature allows no “final word.” The research and experimentation simply continue within a career, from colleague to colleague and, one hopes, from generation to generation.

For me, the next step (in the not-too-distant future) is to repeat many of the experiments that informed the videos in this publication, but this time using carefully formulated old Venetian glass recipes and carrying out the work at a wood-fired furnace in the manner shown in the Butteri painting—except for the period clothing! Please stay tuned.

William Gudenrath

Resident Adviser

The Studio of The Corning Museum of Glass

Corning, New York

February 1, 2019